PSA: There’s a companion podcast! I go into WAY more detail on the “Physics of Startups” podcast - available on Spotify, YouTube, & Apple Podcasts. Here’s this episode link:

Take a look at your calendar this week. What does it say about you?

The way we spend our time reflects how we believe the world works - what I call our “operating philosophy.” Some examples:

If we choose to spend our time heads’ down building product, not talking to customers… maybe our operating philosophy is that the world is waiting on bated breath for us to reveal our brilliance.

If we try to sell, but we go through the motions selling reluctantly… maybe our operating philosophy is that we should be rewarded simply because we’re trying.

If we keep doing the same thing every week despite making no progress… maybe our operating philosophy is that we are incapable of failure, so we can keep doing what we’re comfortable doing and it will all work out.

If we experiment in multiple directions at once, try to build a product for an industry we don’t know without getting firsthand experience in the industry… you get the point.

Everybody1 has an operating philosophy: We all choose to take action (or take no action). Our choices and actions reveal how we believe the world works.

Of course, very few people have deliberately decided on their operating philosophies. We’re rarely even aware of our operating philosophies. If you look at your calendar right now and infer your operating philosophy, the result will surprise you, and might disappoint you. This is a brutal activity.

That’s because for most of our lives we haven’t needed an explicit or deep operating philosophy. In school and work, the operating philosophy is given to us: There’s a grading system or a rating system. Follow the system’s rules, and you’ll be fine.

When we start out as founders, our operating philosophy is equally shallow and unstated. Often it’s mimetic: We look at successful startups and just try to copy them. Or we look for a grading system - a playbook we can follow, or graders we can make happy. As a result, we tend to pursue funding announcements, VC approval, performative working hours, or whatever the day’s in-vogue metrics are.

Sometimes this magically works, we wind up with a fast-growing company, and never need to think about our operating philosophy. But most of the time, nothing works, and we may slowly realize that we know nothing and we’ve been LARPing the whole time. This is, of course, hell. We usually wind up flailing around, looking for some missing tactic that’s going to cause us to succeed (hint: it usually doesn’t). On the upside, this corner of hell is an opportunity to become aware of our operating philosophy - to try to figure out how the world actually works, and adjust how we spend our time.

I’m now nearly a decade into the practice of 0-1. Here’s my attempt to explain how the startup world really works, and therefore, how I should spend my time. I’ve put it all into this Miro board, and will continue refining it, well, until I die, probably:

Let’s walk through the core components of this world-model.

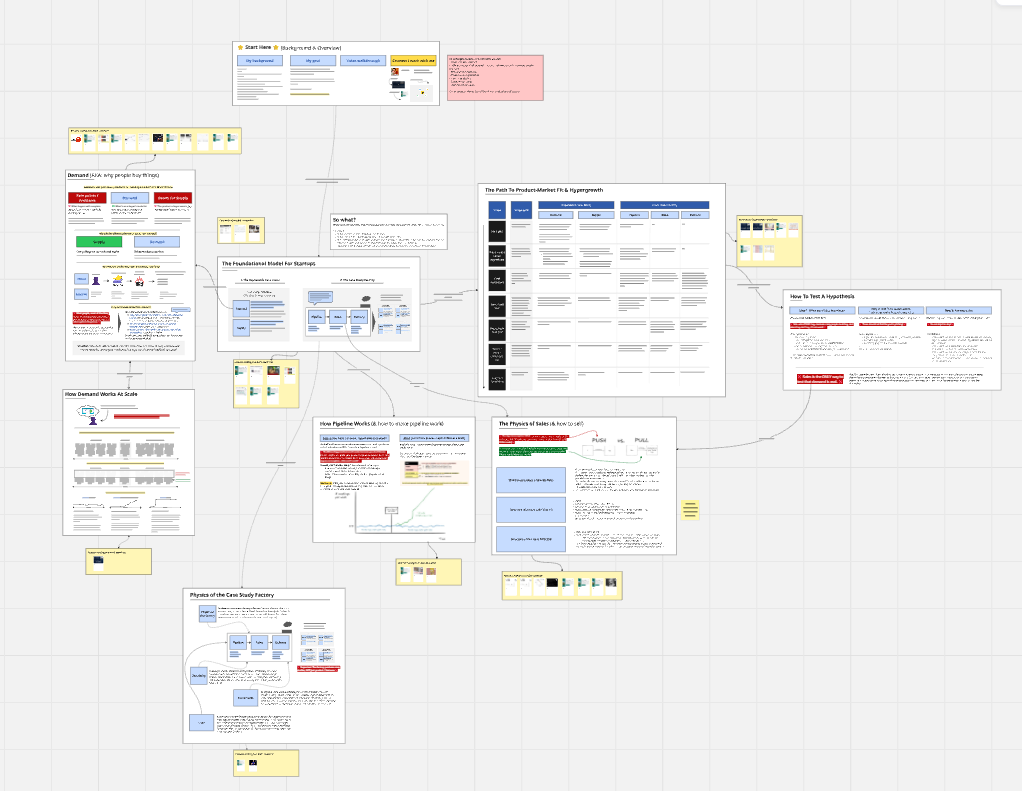

The Starting Point: Demand

Why does anyone buy anything? Why does anyone do anything? This is the only starting point that makes sense. After all, for a startup to work, people have to choose to buy their product or service. We can’t force people to buy things.

This question - why do people buy things? - seems simple, yet common answers are terrible. “People buy because they have pain points.” Sure, but when people have pain points, they often don’t buy things. “People buy solutions to their problems.” Again, sounds right, but also people have problems and don’t buy things. Not helpful!

We need a better definition that works ex-ante - which brings us to a model for demand, understanding why one person does something. And then to understand PULL, which explains why one person would be weird not to buy our thing:

Then, we get into the fun questions about how demand scales, because after all, no persona or niche or group of buyers has ever bought anything:

We can start to understand startups from this starting point - when buyers have demand, they look for supply that fits their demand. Our job is to figure out what demand is, and design supply that fits their demand better than their other options.

When we combine demand and supply, we have a case study - a story of one customer who needed to accomplish something, who bought our product instead of her other options, and was able to accomplish what she wanted to accomplish.

Then:

Our job is to repeat that case study

Our business is a factory that repeats the case study

Hence, a foundational model for how startups work:

We’ve already talked about demand and supply; let’s talk about this “case study factory” idea. (This is probably my least-understood framework.)

We’re taught to think about the customer journey as some sort of funnel, which is actually counterproductive from a physics perspective - it’s as if gravity is going to pull customers down our funnel, which is absolutely not the case. When we think about our business as a factory for repeating a case study, we can use manufacturing theory to understand the physics of a factory - which helps us know exactly what matters, when. (See: Factories vs. Funnels)

The case study factory has three steps: Pipeline, Sales, and Delivery.

With all of this information, we see how and why a startup works. We can start getting into how all of this comes together over time - which tells us what matters. Let’s explore the process by which startups go from “idea” to “hypergrowth” - all we need are the components of demand, supply, and the case study factory:

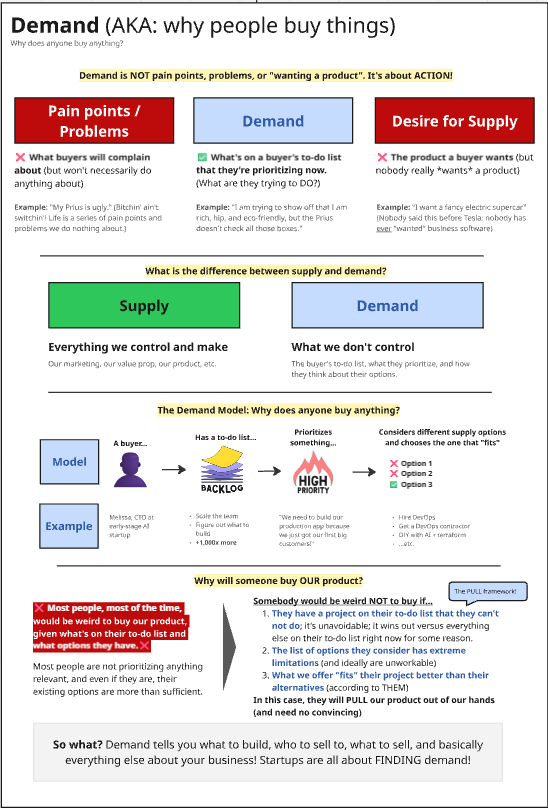

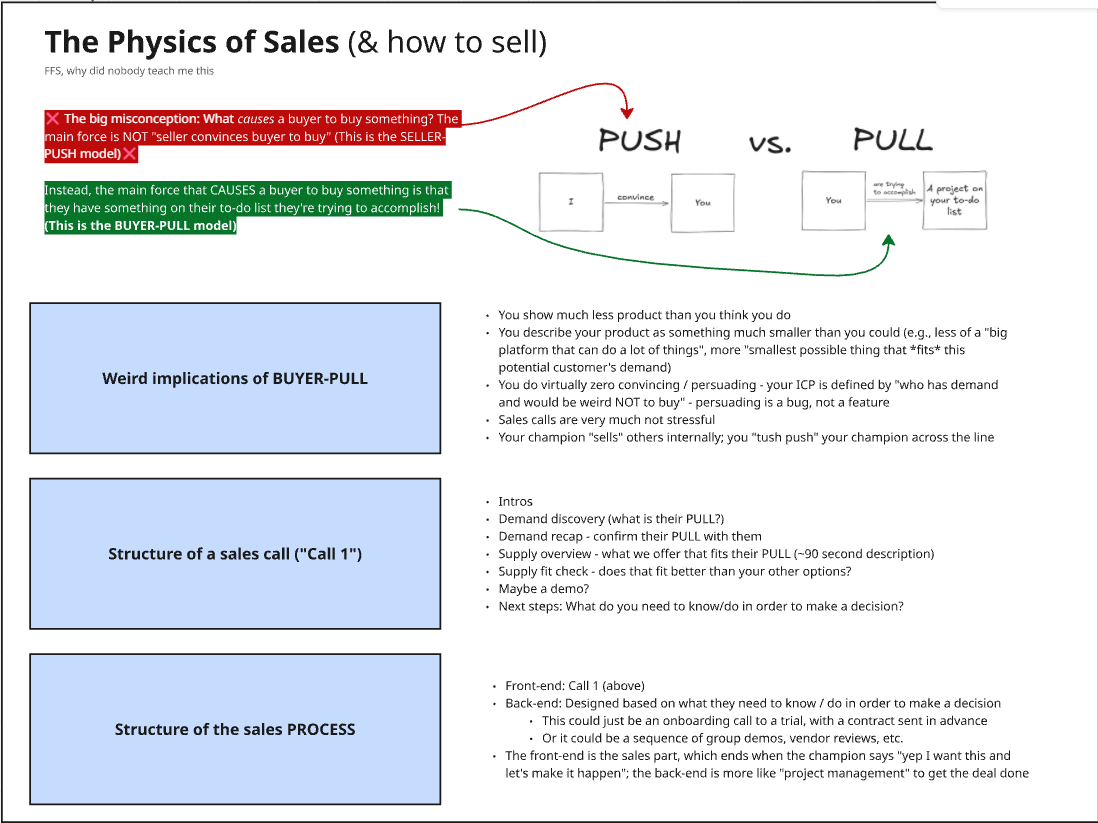

And how do you test a hypothesis early-on? By selling!

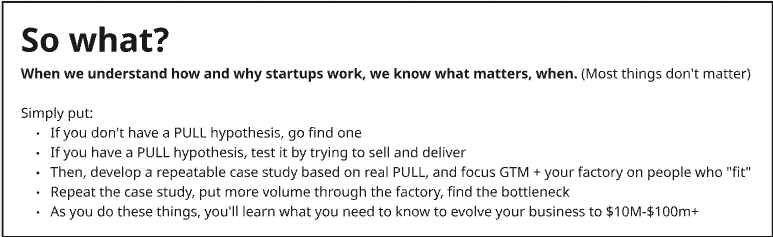

This is my model for how the world works.

The point of understanding all of this is to be able to answer a simple question: “How should I spend my time?” When you think about it, the only difference between successful and unsuccessful founders is how they spent their time. Time is all we have, and we have less of it than we think.

PS: My next live “product-market fit + sales” program starts October 20, & I have just a few remaining 1:1 slots for B2B founders to figure out 0-1 sales & PMF. If you’d like to potentially work with me in 2025, reserve time on my Calendly in the next few weeks HERE - more info & course signup is HERE.

Realizing that our customers also have operating philosophies, that cause them to prioritize certain things on their to-do lists (and avoid other things). Also realizing that operating philosophies exist across domains - it’s not just a work thing. If I’m distracted when my wife is talking, that’s revealing an unpleasant operating philosophy, for example.

That's great! Any tips on finding an initial PULL hypothesis?