How Loom Found PULL

The Physics of Startups Series #002

There are infinite ways to (mis)interpret what caused a company to succeed.

Today, I’m focused on the history of Loom, the Chrome extension that lets you easily record and send selfie/screen-recording videos. They were acquired by Atlassian for $975 million in 2023.

Here’s my version of their story, then my PMF reflections.

OpenTest v1 → v2

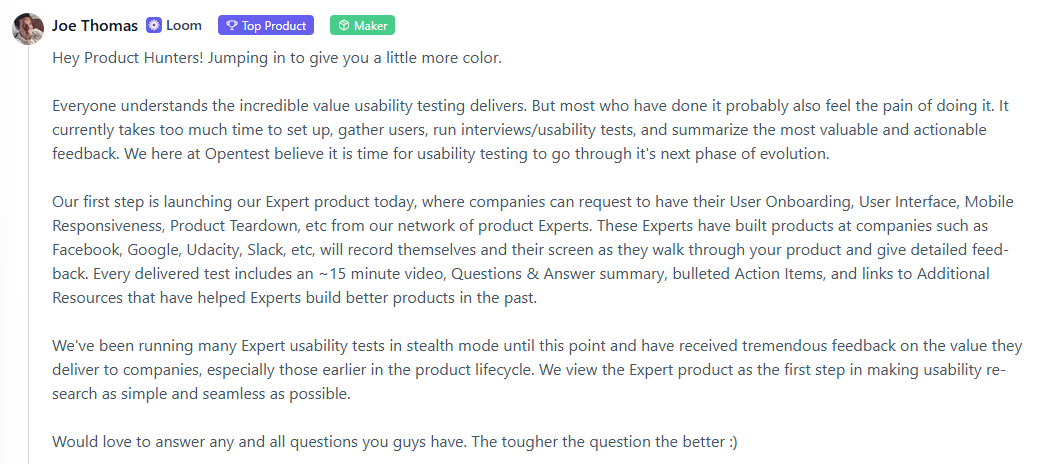

Loom started as OpenTest, a user testing platform. Let’s go back to OpenTest’s original Product Hunt launch:

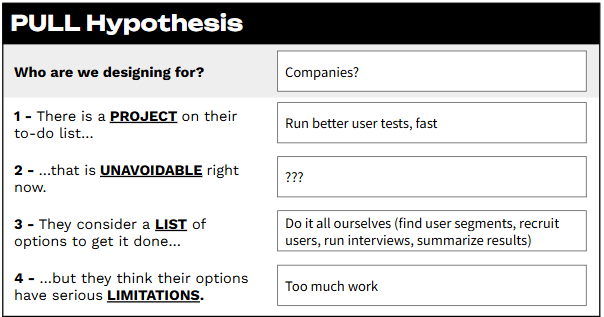

This looks exactly nothing like the “hip screen recording tool” we all know today. Let’s build out what OpenTest’s demand hypothesis was, using the PULL framework:

Demand was to run better usability tests, fast; supply was a marketplace for usability experts. You’d pay $100 an get back a video from the expert (example video here).

Their launch went decently on Product Hunt, but, in a few months, OpenTest made $400 in revenue, meaning exactly four people bought their expert usability tests.

The team got feedback from people at Facebook and Twitter who said they would never use OpenTest, because they had experts in-house. They didn’t need to go external to a service like OpenTest to find experts.

Shahed continues, “They told us… they would be interested in purchasing the ability to run a user test, segmented to a specific cohort in their user base.” So OpenTest pivoted towards that, and launched OpenTest v2. Here’s their revised PULL hypothesis:

And it worked! Just kidding, it didn’t. Six months later, OpenTest was running out of money and begging people to use their product for free.

We’ll come back to the question of why OpenTest v1-v2 didn’t work a bit later. For now, let’s see what happens next.

OpenTest v1 → OpenTest v2 → Openvid

A Harvard research team was one of the few OpenTest users. The research leader used the product as intended: To collect user feedback. But once he’d done this, he then used OpenTest’s Chrome extension in a way that was surprising to the OpenTest team. The researcher recorded a video of himself summarizing the feedback he’d collected to send to his team.

And this, apparently, was the lightbulb moment that totally reframed how OpenTest’s cofounders saw demand and their product. They ripped this feature out and launched on Product Hunt again, this time under the name of Openvid:

It seems like Openvid’s PULL hypothesis was something like this:

Openvid’s launch went to #1 of the day on Product Hunt, and ~2,500 people downloaded and used their product that day.

Product-market fit, right? Wrong.

Something wasn’t quite working: People were downloading the product, using it once to test it out, liking it, but then most were not using the product again.

The Openvid team interpreted this as: Users don’t know what to use Openvid for in their daily workflows. They needed to go from “this is cool but it would be weird if I used this again,” to “it would be weird if I didn’t use this every day.”

The team analyzed their few repeat users: Engineers were using it for code reviews, designers were using it for design handoffs. The founders injected these ideas into their marketing and user onboarding, so new users didn’t have to think about what to use it for. (Lesson: Nobody’s going to think.)

Which meant their PULL hypothesis, when it led to retained users, looked something like this:

As the story goes, they rebranded to Loom, eventually figured out monetization, rode the COVID remote-work wave, then got acquired by Atlassian for $975 million, who promised to bring JIRA’s UX expertise to Loom.

There are many interesting implications of Loom’s story, but I keep thinking about two things:

Why was OpenTest wrong?

What else could have worked?

1 - Why was OpenTest wrong?

OpenTest’s demand hypotheses seemed logical. At the time, you and I might have looked at them and said, “Yeah, totally get it - seems like a real opportunity.” They almost certainly interviewed a bunch of prospective customers who all said, “Yes! User testing is massively painful, and I would love to have a better solution!”

In fact, their first pivot (from “we provide experts” to “you just use our tool internally”) was based on feedback from potential customers seemingly telling them exactly what they wanted.

Despite this, OpenTest didn’t work in practice. Why?

My guess is that demand simply wasn’t strong enough. People could logically agree that usability testing is slow and cumbersome, but not change. “Speeding up / improving our usability testing” wasn’t on their to-do list.

How can we know this for sure? As you know, my preferred approach is not to launch on Product Hunt and then look anxiously at my web traffic metrics, it’s to use the long-forgotten Japanese technique called 販売 (in English, “sales”).

When I look at web traffic, I see people viewing the site and… nothing else. When I have 1:1 sales conversations, I see how they react, where they get confused, where they start leaning in. In these sales conversations, I’m looking for PULL, which is the feeling of a dam bursting… Whoa, wait a second - you mean in one click, for $100, I can get an expert usability test? How do I start? Where do I pay?

Instead, we heard, “wow, this is exciting, but we would only use it if it helped us run our own user tests,” which sounds PULL-adjacent, but that’s when you follow up and say, “Cool, we also have that, that’s $500 / month, here’s the Stripe link.”

When you offer the Stripe link, you’ll quickly see the difference between a dam bursting and a damn lie.

—

Loom found PMF as many others have: With an out-of-left-field anecdote. Someone using the product differently than expected; someone saying “holy sh*t” when you describe it; someone from a different industry reaching out.

The thing I most enjoy about the Loom story is, in my mind, seeing their PULL framework reshape as they saw the Harvard researcher using the product… and, to their massive credit, them going “all in” on it - stripping down their product to perfectly fit what the researcher was pulling for.

2 - What else could have worked?

Is Loom the only business that could have worked here?

Usertesting.com was founded about ten years before OpenTest, and went public in 2021. So maybe the alternatives were “good enough” for OpenTest v1 (the expert marketplace)?

But then there is Wynter, founded in 2021, which initially started as a way to test B2B website messaging with buyers. A different, but not that different, permutation of OpenTest v1. This tells me there probably was some permutation of an expert marketplace that could have found real PULL.

What about OpenTest v2 (the user research tool)? Well, Maze was founded in 2018, a few years after Loom. It seems like exactly what OpenTest v2 was trying to build. In Maze’s Product Hunt launch, they promised designers something much more specific: “Beautiful & actionable analytics for InVision prototypes.” The funny thing is that this launch got about the same number of upvotes as OpenTest’s initial launch; it just seems to have led to people actually using it - perhaps because it was designed around real PULL. (Or perhaps the right-fit GTM approach for this kind of business is NOT Product Hunt.) The lesson, again, is that there was some permutation of OpenTest v2 that could have found real PULL.

Finally, there’s SendSpark, founded in 2021, a permutation of Loom’s “record video, send it” that’s designed specifically for sales prospecting. This tells me that there *even* was an opportunity for Loom to build a different permutation of Loom and still find PULL.

What do I make of this?

There are many shapes of successful businesses, all designed around PULL.

Trying to figure out the “global optimum” when there are many viable paths is certain to drive you crazy.

The reasons OpenTest v1 & v2 didn’t work were, perhaps, more to do with coming at it from the direction of “here’s how we think the world should work”, versus from an insight about PULL. This led to messaging and a product that were slightly off; slightly off doesn’t take off.

3 - On Revisionist History

A bonus: Someday, when your company gets acquired for gobs of money, someone will ask you a question about your startup’s winding journey.

In that moment, you will be tempted to say something like this: “We went through 2 major pivots, but the general thesis remains the same today: How do we allow someone to communicate something that’s rich in context?”

(This is what Loom’s cofounder said in this post-acquisition interview.)

I heard this and laughed out loud. It’s total BS - the kind of thing you’ll say not because it’s true, but because if you admit the truth, you’ll weep.

—

Rob

I found your 103 page slide deck and have to tell you it's awesome! Every page! For fun, I like to reverse engineer why some recent scandals (e.g. Bernie Madoff) found pull (consistent returns, little risk) it's a fun exercise to do when finding your own pull.

Super interesting..yet the question is: how do you systematically find that pull? Just hope a lucky strike hits you like the Harvard Engineer?