How Plaid Found Pull

A new (experimental) series

There are so many ways to (mis)interpret what caused a company to succeed.

I was listening to Ben Thompson’s interview with Plaid’s cofounder, Zach Perret, and thought it might be interesting to give you my interpretation of Plaid’s path to PULL and takeoff.

This post is an experiment - let me know if I should do more teardowns like this!

For context: Plaid is a fintech company that you’ve probably used to connect your bank account to some online service. The company’s most recent funding round valued it around $6b.

Where Plaid started: Consumer apps

Plaid started with a noble mission: Making the financial system work for normal people in the wake of Occupy Wall Street.

Their first products were finance apps for consumers. For example, helping consumers budget better, spend wisely, and save money.

We can use my PULL framework to infer Plaid’s initial hypothesis about demand:

How did this go?

For their initial mobile budgeting app: “It turns out when you send users notifications to tell them to buy less coffee, they either mute their notifications or just delete your app.”

For an app to help people save money: “It turns out if you tell someone, ‘Hey, the grocery store down the street is cheaper than the grocery store you shop at’, their response is, ‘Yeah, I know, I don’t want to shop at the cheap grocery store, it’s kind of gross’.”

AKA: Their initial consumer apps went poorly.

Why didn’t these things work? They almost certainly had compelling and highly logical pitches, with clear ROI. It mirrored what people almost certainly said they wanted in discovery interviews.

And yet consumer behavior suggested otherwise.

My interpretation: This PULL hypothesis “made sense”, but didn’t reflect the real to-do list in buyers’ brains. We can really only understand what’s on someone’s mental to-do list by observing their actions… not by listening to them talk about what they will want or building something they should want.

There’s a reference to Matt Mullenweg’s theory that the only consumer apps that succeed are based off the seven deadly sins… which tells you something about what’s really on consumers’ mental to-do lists, and how different this is from what most of us will admit to.

B2B Pull

The Plaid team had a friend at Venmo, who told them (1) that they were bad at making consumer apps, and (2) that Venmo wanted to use the backend they’d built for connecting to consumers’ banks.

This is often where PULL emerges… a random anecdote. We just have to listen for it.

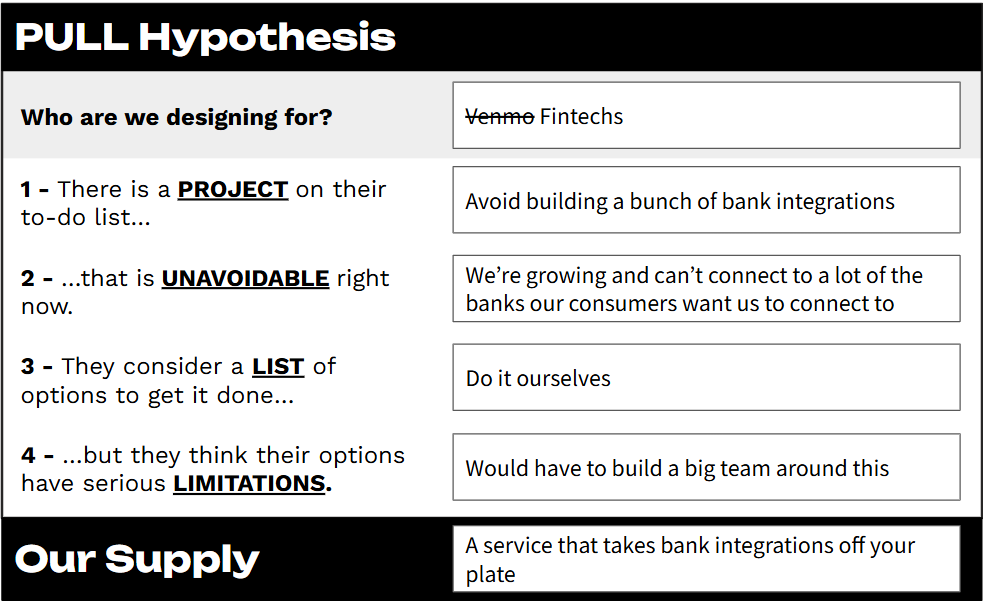

So let’s put Venmo’s demand into the PULL framework.

The questions Plaid needed to ask about Venmo’s PULL were:

Is this real demand?

Is this repeatable demand?

Is it real? It seems like the Venmo champion pulled the Plaid team through a long, winding purchasing process - which tells us that the champion was willing to suffer enough to buy their product that the champion’s demand was real.

Is it repeatable? While going through Venmo’s winding purchasing process, Plaid signed up 15-20 other fintechs with the same pitch and product… indicating that, at least for fintech apps, this demand was repeatable.

I imagine their pitch to these other apps at the time was quite simple: Hey, we’re hearing that Venmo doesn’t want to manage all these bank integrations themselves… and we’re working with them on a way to handle all their bank integrations as a service. How are you different from Venmo?

Supply

If we know what demand is, we can then ask: What supply can we offer that fits this demand better than alternatives? This supply doesn’t need to be perfect… and in fact, the stronger the demand is, the less perfect supply needs to be.

In Plaid’s case, the alternative was for the fintech to build and maintain all these bank integrations themselves. This was a huge effort to cover all the banks that buyers could possibly have - tens of thousands of banks to fully cover the long tail. Essentially, the fintechs’ existing option (DIY) was unworkable.

Demand was strong enough - an unavoidable project with unworkable options - that Plaid’s supply didn’t have to be perfect. It just needed to get integrations off the fintechs’ plates - fitting their demand. And so these fintech apps bought despite the fact that many of Plaid’s bank “integrations” weren’t actually integrations… they were often, to put it kindly, janky automations.

Plaid’s Unfolding

Early on, the Plaid team focused on fintech apps who had intense PULL for these integrations. They did this because (1) fintech apps had strong PULL, and (2) they assumed banks didn’t have PULL. This same thinking caused VCs at the time to consider fintech uninvestable.

Turns out, banks actually had PULL, and Plaid evolved its product offerings to take advantage of bank demand and other demand that followed; their unfolding story continues and their product evolves. This wasn’t planned, it just emerged over time.

My summary:

Plaid fell into the trap we all fall into: Pushing something we think people should want

Plaid’s real unfolding journey started with one PULL anecdote

They made sure this PULL was real, strong, and repeatable (ahem, by selling)

Because PULL was real and alternatives were bad, their supply could be ~janky

In time, the business evolved in an ex-ante unpredictable way; it makes logical sense looking backwards but was nothing like that looking forwards

—

PS:

Exploring offering a new “founder-led sales pitch” service. Sign up in June and get it for a stupid price (more info here).

> let me know if I should do more teardowns like this

Yes please - these examples are great for seeing parallels and grokking the method

The one thing I'm surest about after nearly 20 years of in-depth qual research: Mullenweg is right. For any founders out there...nobody wants to budget better. Nobody. They want more money. (And the ones who do want to budget are overserved for choice/doing a good enough job already.)

I've also learned to bet on any mass plumbing startup. Google is a plumbing startup. Mass integrations to bank and fintech backends is also a plumbing startup. (Good ones nowadays resemble real-world plumbing, i.e. usually invisible and something people never think about.)