Killing wishful thinking

On probability and infinite problems

I keep coming back to an idea that, I think, explains much of the unnecessary pain we founders put ourselves through.

The early stage is less “zero to one” and more “infinity to one”, in that our job is to get from infinite things that could theoretically work to one thing that actually works. It is a narrowing exercise, not a broadening exercise.

The hard part about this is, well, everything. Narrowing means deciding not to do 99.9999% of good ideas that probably could work.

How do we decide what to do, in a world where so many things could work?

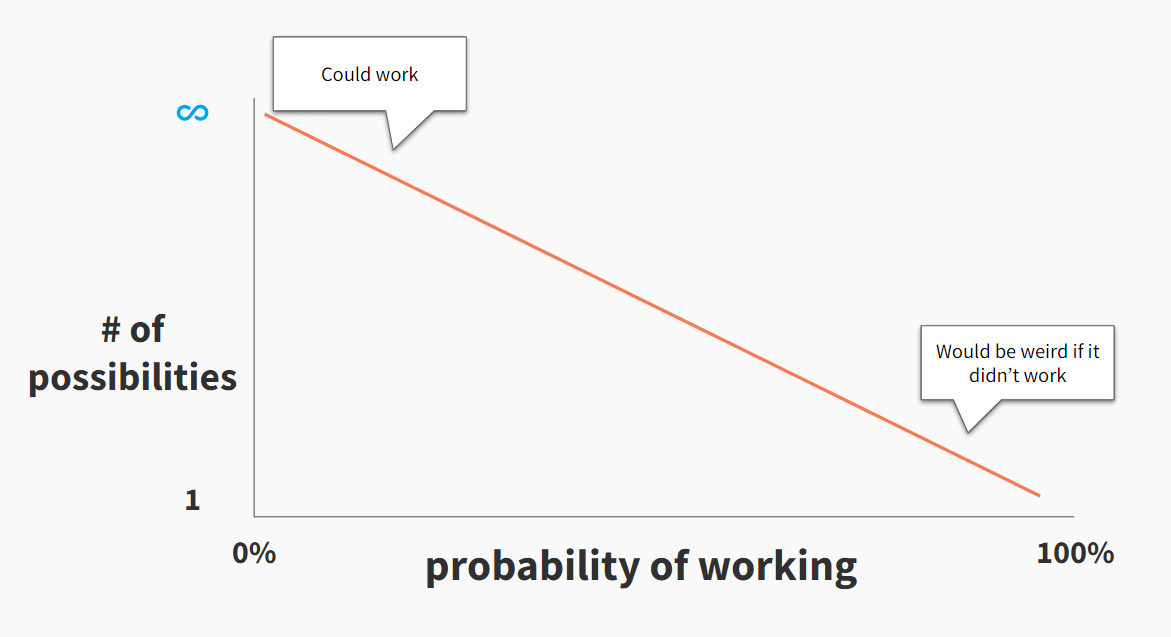

The following graph lives rent-free in my mind:

Implications:

When I ask myself, “what could possibly work?” the possibilities are infinite.

But when I come at it from the opposite direction and ask, “what would be weird if it didn’t work?” there aren’t many options.

This is a tool to prevent wishful thinking, and it works in basically every aspect of business:

Ideal customer profile: Who, in what situation, would be weird not to buy our product?

Outbound: What message could we send that it would be weird if they didn’t respond?

Offering: What offer could we put in front of prospects that they’d be weird not to buy?

Product: What MVP/feature can we build where it would be weird if they didn’t get the value out of it?

Onboarding: What set of steps can we construct where it would be weird if they didn’t complete them, and weird if they didn’t lead to a post-sale “hell yes”?

The “would be weird if didn’t work” reframe compounds. For example, when we’re targeting people who would be weird not to buy our product, we can do more creative things to build our pipeline. We don’t have to, for example, send cold emails that sound identical to everyone else who’s targeting everyone who maybe could buy. Plus when we have conviction on who would be weird not to buy, in what situation, we tend to waste less product surface area on features that might be useful, and generally waste less money and time on stuff that maybe could work.

On the other hand, if we target people who maybe could buy, we feel like we need to push and persuade. Make our product more flashy, add tons of features. It doesn’t matter because in the end, they probably won’t do anything. Reality check: the default case is that people won’t buy our product. It would be weird if they did. Our job, then, isn’t to convince people they should want to buy our product. It’s to find people in situations in which they’d be weird not to buy it.

Plenty more implications here. Give this reframe a try, let me know what you think!

—

PS:

The last PMF Camp of 2024 is now full. Every single camp this year sold out. What a year. Working on some new ideas for 2025 to expand this experience to more startups, stay tuned.

Would love feedback on Waffle’s new website! (Yes, it’s ugly.)

One of your best blogs yet, Rob.

*scientist mind blown meme.gif*

I love your approach to web design btw. Clear, simple, obvious. Boom.