How to understand customers

Forward deploy everyone

You can now pre-order my book, The Power of PULL, which is coming out July 7! I am working on some cool gifts for people who pre-order it - stay tuned. And yes, I am working on making preorders available outside the US…

Podcast discussion of this post here:

Last year, the Forward Deployed Engineer was all the rage - where a few of your engineers go work alongside customers to customize and implement your software.

This is a great trend, because it means that we as an industry are getting close to realizing that we should get firsthand customer knowledge - experience doing customers’ jobs with them.

In 2026, the goal should be to forward deploy everyone. That means every single person in your company. This is true whether you’re a 2-person team, a 25-person team, or a 300-person team. And it’s true whether you’re at the idea stage or post-PMF.

Here is why and, just as importantly, how.

Part 1: Why Everyone Should Forward Deploy

My wife recently said this sentence to me: “I found two delis that have sandwiches.”

I think about this sentence quite frequently. It is, when you look at it, total nonsense. Two delis that have sandwiches? Great, I’m pretty sure all delis have sandwiches!

But when she said it, I understood what she was saying because we had shared context. The context: We were driving on a road trip, it was nearing lunchtime, and we didn’t know where we were going to stop for lunch.

Given our shared context, we were on the same page despite the content of the sentence.

Forward deploying everybody gives your company shared context about how your customers behave and what they are trying to accomplish. This enables you to build the right thing despite imperfect communication. The alternative is building the wrong thing, even with near-perfect communication.

Here’s what happens, for example, if you have a two person team where one person is “the technical founder” and the other person is “the GTM founder”, and only the GTM founder spends time with customers.

The GTM founder talks with a customer and realizes that the customer is actually trying to do {X} with their product, which currently only does {Y}

The GTM founder tries to explain it to technical founder, and it takes forever to communicate properly - what {X} is, why it matters, what we should build.

Technical founder feels like they don’t understand why we can’t just sell {Y}, or why customers care about {X}, or why customers can’t just do {Y/X}. It feels like disconnected sprawl.

Technical founder presents {Y/X} approach, which the GTM founder thinks they understand, and so it gets built, but it doesn’t really fit what customer is trying to do, and so there’s a lot of frustration.

Cycle repeats with, this time with a “fix” of more formal writeups, or more vibe coded prototypes, etc.

I have seen this exact pattern cause cofounder breakups. And this example is just in a two-person company - this problem gets infinitely worse as you hire! It plays out in and across every department: Ever wonder why sales and engineering almost always wind up hating each other? Or why startups by default build things nobody wants… despite setting out to build something people want?

If you don’t have a firsthand customer intuition, you will only build the right thing if you get lucky on the millions of decisions it takes to build a great product and company. If everyone on your team doesn’t have a firsthand customer intuition, you can’t speak the same language about what you’re trying to do. There is always a translation error, and the translation error compounds in ways that lead to terrible products and terrible businesses. Translation errors can only be prevented by:

Perfect communication, or

Never-ending luck, or

One all-knowing founder as the bottleneck for every decision, or

Giving everyone firsthand customer intuition

Out of these, I’d pick the “firsthand” option.

“But Rob, can’t we just do customer interviews and record them?” Sure, but that’s not enough. Think of the arrogance of this statement: I believe I can build a product you’ll use just by interviewing you; I don’t believe I actually need to walk in your shoes. This doesn’t work - it’s the cofounder translation problem above, just magnified 100x.

Part 2: Ways to Understand Customers

That said, if I just say, “Forward deploy everyone”, everyone’s going to work alongside customers but nobody is going to have any clue what they’re looking for.

I spent a lot of time in-person with customers, in their offices. And I wasted most of that time, because I didn’t understand what I was seeing. Sure, some tasks looked inefficient and annoying, but it wasn’t obvious that “inefficiency = product opportunity.”

When you watch people working, or work alongside them, you just see them working. You need a conceptual framework to understand what it means and what to do about it.

The PULL framework has forced me to create models of customer behaviors and intentions. Turns out, these can be used as a general-purpose tool for decoding customers!

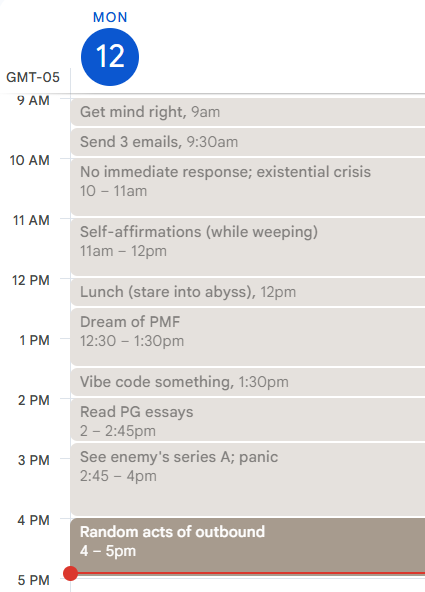

The calendar (what they do)

When you observe customers, you want to start just by observing what they do across time. I see this as a calendar, where every minute is full - it could be “doing a task” or “looking at phone while on a zoom call” or “staring off into the distance”. Their calendar is our ground truth:

The calendar is our ground truth of what the customer is doing at any one point in time. This is where I got stuck: I observed all the customers’ work tasks. But I didn’t know what these work tasks meant - and, more broadly, if there was an opportunity for a new product or feature that they’d buy, use, and love.

Which means we need another framework, a layer on top of the calendar, to reflect customers’ intentions - what they are trying to accomplish at a specific point in time.

The to-do list (what they are trying to accomplish)

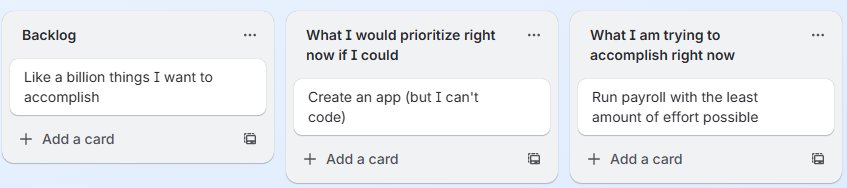

This is the framework I’m most known for: the customer’s to-do list! (Please, hold your applause.) Imagine a literal to-do list or project management software - I imagine a Trello board:

Everyone’s mental to-do list has a million things on the backlog - there are so many things I want to accomplish! But I can only do one thing at a time. The customer’s calendar at any one point in time reflects the ONE thing they are currently prioritizing on their to-do list. Their actions are ground truth because they are visible and real; they reflect priorities and intentions in customers’ minds. We have to infer what’s on their to-do list based on what we see them doing.

Before we go further, there are two ways people misunderstand the customer to-do list concept:

They think I’m referring to the customer’s literal to-do list. And you’ll say, “but their to-do list is out of date; it is super vague; nobody has a a to-do list that reflects what they are doing on a minute-by-minute basis.” Yes, I agree - I’m not talking about their actual to-do list, I’m talking about the to-do list in their soul. What are they actually trying to accomplish?

They think customers want products and features. “Buy a CRM” is not on the to-do list in anyone’s soul, nor is “buy a Prius”. More broadly, we need to think about the to-do list as being product-agnostic - it is about what they are trying to accomplish in their lives, it is not about products at all. For a CRM, the project on their to-do list might look like: “I need to be able to manage my sales pipeline so I don’t lose track of deals.” There is no product in that project; there can never be a product in their project.

So! We now have a clear sense of what they are literally doing in their jobs, and we are inferring what they are trying to accomplish in their souls. “Can I build a product now or sell something now?” Not yet! Because we haven’t yet found a space where a product would fit.

Where is there a space for a product? I believe product opportunities are found where there are conflicts between the to-do list and the calendar. Think about it:

If there is no gap between their to-do list and their calendar, they are doing exactly what they intend to do - they are in perfect equilibrium, applying no force against their status quo. It would be weird if they changed.

If there is dissonance between their to-do list and their calendar, they are struggling. They are applying force against their status quo.

(This is a big unlock to the physics of startups… it starts to explain where PULL comes from!)

There are two ways this conflict seems to play out:

When they are doing something that doesn’t fit what’s on their mental to-do list. (Example: Jump for automating financial advisors’ client meeting notes)

When they are not prioritizing something on their to-do list right now that they would prioritize right now if they could - but something is blocking them. (Example: Lovable for non-technical non-designers building websites or simple apps)

By observing these places of conflict, you can generate what I call a PULL hypothesis, to articulate who you believe will rip a product out of your hands. A PULL hypothesis has four components:

The project on their to-do list that they are trying to accomplish (but are blocked)

The situation in which they prioritize this over the million other things on their backlog: Why is it urgent or unavoidable now? Why can’t they just do nothing?

The list of options they consider or try - e.g., DIY with a spreadsheet, hire someone.

Why their existing options aren’t good enough: Why they don’t “fit” the project, their limitations - such that if we offer something that overcomes these limitations, they will rip the product (or feature) out of our hands.

Now we are in the realm of a product idea or feature idea. You can test if your PULL hypothesis is real by trying to sell; I recommend running a sales sprint (which I have outlined here).

But more broadly, the calendar and to-do list are pretty straightforward ways anyone can understand what customers are doing and why - so that when everyone forward deploys, you actually learn things.

You will get into debates about what’s really on customers’ to-do lists and the mechanics of their to-do lists. These are good debates to have - much more productive than debates about which features to build. As you have these debates, you are building your and your team’s customer intuition, so that you can increasingly predict what customers will find to be amazing and delightful… without needing perfect specifications for everything.

Part 3: How to Forward Deploy

Some quick field notes, as this post is already too unwieldy:

There are often different people who are buyers/champions vs. users. You need to shadow both, obviously, but remember that champions’ projects cause purchases and renewals, while users’ projects and calendars often prevent purchases and renewals.

How do you get someone to let you shadow them? Just ask. “Hey, I’m a MIT MBA working on a startup idea, and would love to come shadow you for a few hours - would you be open to that?”

Forward deploying is the bare minimum. I have seen founders get jobs or consulting roles with the people they want to eventually sell to, so they get as much firsthand knowledge as possible. This has the helpful side-effect of paying your bills.

Corollary 1: Second-order and higher-level ideas

The to-do-list / calendar relationship is probably not 1:1. Said differently, you might look at multiple things on someone’s calendar and connect them to a single project. Or you might look at a set of things on someone’s calendar and connect them to something higher-level or second-order than a mere “project”: A goal, a priority, even a philosophy.

Clearly these things are important. As is a deeper understanding of the calendar and to-do list: Does it matter if a project recurs frequently? What level of conflict is necessary between the calendar and to-do list before someone will act on it? Etc.

Here you can see the current bounds of the theory - the operating philosophy post gets into some rough thinking about structures beyond the to-do list that can be used to predict actions.

Corollary 2: Pain points and more revenue

Hopefully the above approach seems straightforward: You just need to teach your team about the calendar and the to-do list, give them a few examples, and forward deploy them.

But in the back of your mind, you’ll probably be tempted to skip this and go with some simple concept like “hair-on-fire pain points” or “problems” or “inefficiencies”, or some business heuristic like “everyone wants to improve profitability or reduce risk” or “sell increased revenue” or “craft an offer they can’t refuse” or “make a 10x product!”

These simplifications may occasionally work, but usually don’t. You will find many revenue-increasing opportunities that nobody will buy, just as you will craft many seemingly “irresistible” offers that turn out to not be irresistible, and you will waste years of your life building a 10x product that nobody wants.

If I’m spending my life building something, I’d really appreciate a way of thinking about “what customers want” that is (1) >80 IQ and (2) would be weird if it didn’t work. That’s what I’m shooting for here, at least.

Corollary 3: Other useful tools for understanding customers

The calendar and to-do list are, I believe, foundational. They are models that explain all human action - not just purchases, not just purchases of our product, and not just actions taken while at work. They can be used to understand why people text while driving, for example. They can be used to understand yourself: Why am I avoiding sales - and what does my calendar tell me is really on my to-do list?

That said, it is helpful to add onto this base some specific tools for understanding specific things that customers do:

For understanding what caused someone to buy a particular thing: Check out “jobs to be done” (JTBD) interviews, and watch Bob Moesta conduct one. This is a methodology that reverse-engineers the sequence of events that cause someone to prioritize something on their to-do list and buy something. It is a useful tool after someone has bought something, for predicting (1) when someone else will buy something, and (2) what actually matters in a purchase.

For understanding unexpected customer feedback: Check out David Cancel’s Spotlight framework.

For understanding feature requests: Remember that they are requesting supply, not expressing demand. Watch Ryan Singer use JTBD-style interviews to reverse-engineer the sequence of events leading to a feature request, which helps him understand the real demand behind the feature request.

PS: Work with me!

If you’re trying to find product-market fit and figure out sales, let’s chat! Three ways I can help:

I can review a recorded sales call with you. This is a super fast, lightweight way to get my help fixing your sales call, pitch, demo, execution, etc.

I’m behind dozens of $0-$1M ARR journeys as a PMF advisor. If you’re looking for ongoing support from someone who’s made this happen a bunch of times, reach out - booked until mid-Feb, if you’d like to work with me later in Q1 please reach out soon!

I run PMF Camp - a bootcamp (next starts in Feb!) and weekly live event series where we tear down founders’ sales calls and build your intuition for what customers want and how to sell.

If you’re interested in any of these, grab time HERE or email me at rob@reframeb2b.com. If you want more info and testimonials, see HERE.

great read