Push, Pull, and PULL

Why startups aren't intuitive = why business theory is stuck

What better way to start 2026 than by pre-ordering my book, The Power of PULL!?!?!

I think you and I are capable of building magical, world-changing companies. The next Apple, NVIDIA, Airbnb, Starbucks, or perhaps the companies that make today’s giants look quaint.

The main thing that’s preventing us from building such a company, I believe, is what’s in our heads: The craft of building wonderful companies is unintuitive (and therefore, nearly impossible) given the way we’ve been taught to see the world. This is a function of business theory being stuck.

Now, you might be thinking - “But Rob, how on Earth can business thinking possibly be stuck? After all, Harvard Business School teaches a class on happiness - clearly we must have solved business theory if this is the case!” No, business theory is not solved, and in fact it has been stagnant for over a century.

Business theory last made real progress in 1911 - the year when Frederick Winslow Taylor’s groundbreaking book, The Principles of Scientific Management, was published. This is the most recent great work of paradigm-creating theory in business, the foundation upon which basically all modern business thinking has been built.

The problem is that Scientific Management’s model of the physics of business is incomplete. Because of this, the way we think the world works does not reflect the way the world actually works. This has many consequences, but most relevant to us is it makes startups unintelligible. It’s why copying successful startups’ playbooks doesn’t work, success seems random or magical, selling is unnatural, and “build something people want” sounds obvious but feels impossible.

In this post, I’m going to try to explain Taylor’s model and its successors that are closer to reality… but haven’t yet caught on. (I learned none of this at HBS, for example.)

I believe that if we really understand this, building a magical company will be much less unintuitive.

That said, this argument could easily fill a (hefty) book. Consider this an appetizer.

Taylor’s model

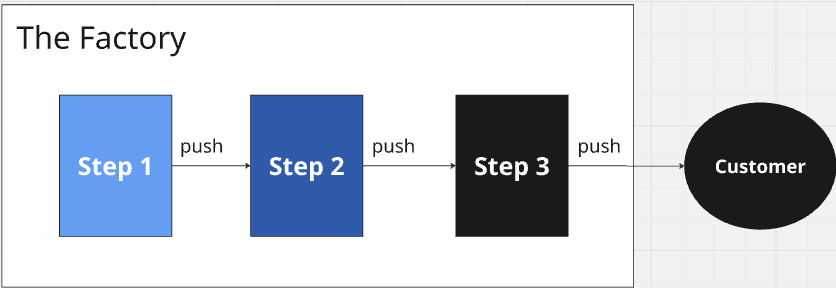

When we look at a factory, this is what we see:

Each step pushes its output to the next step, and out to customers.

Frederick Winslow Taylor saw Midvale Steel Company this way in the late 19th century. He also noticed that each step in the factory was managed very loosely, where each trade decided how to handle their step in the production process.

Taylor decided he could make each step more efficient and effective, so that it could push more output to the next step. He was effective to an almost unfathomable degree. In Scientific Management he details his redesign of the simplest job composed of a single task: lifting a ~90-pound piece of pig iron, carrying it a few yards, and putting it down. Taylor was able to improve the approach to this simple task in a way that nearly 4x’ed output per worker (12.5 tons → 47 tons per day). If Taylor’s approach worked that well for such a simple task… imagine the impact of Taylor’s approach on an entire production process!

This ushered in business as we know it today, enabling mass production and the rise of the professional manager.

And then.

Push vs. Pull

Fast forward about half a century from Scientific Management. Something inconceivable was happening. Over the span of two decades, Japan had emerged from postwar rubble and was now absolutely dominating global manufacturing. There’s one example I keep coming back to: A Lexus took fewer man-hours in its entire end-to-end assembly process than a top-of-the-line German luxury car spent getting all its assembly errors reworked after assembly was “complete.”1

Japanese cars were significantly cheaper, and more fuel-efficient, and higher quality than all other cars on the market. In fact, they were so superior to American-made ones that the Japanese government self-imposed export restrictions to try to let American car companies catch up.2 Think about how insane this is.

What was the difference between Japanese manufacturing and everyone else? Was it one of Japan’s manufacturing techniques? Their work culture? Or just their low wages?

When asked by an American executive why the Japanese were so good at manufacturing, Taiichi Ohno, the legendary engineer from Toyota, said: “We learned it from you!”3

Ohno had visited Ford’s production plants. He was inspired by the exact factory that Taylor’s ideas had created. When he looked at Ford’s factory, Ohno understood the physics of the factory differently… which caused him to understand the physics of business differently.

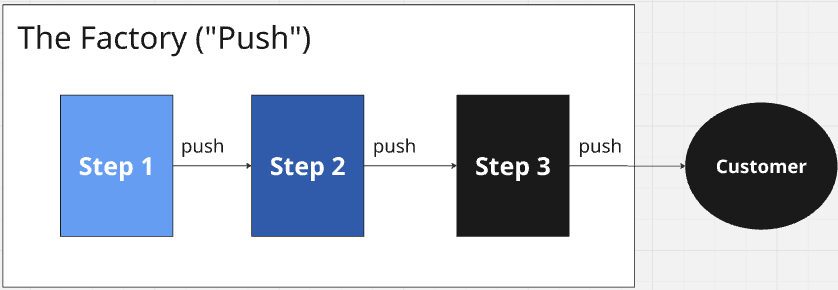

We are taught to see the factory the way Taylor saw it: as a production line that we act on. We are the main causal actors in this model. Our plans, goals, intentions, and actions make things happen. This is the “push” model: We “push” products through the factory and out to customers. We cause production to happen.

This seems obviously true. Of course we cause stuff to happen! But, as it turns out, this is only locally true.

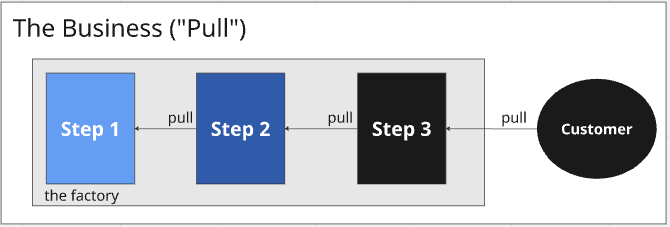

Ohno saw things differently: The factory, in his mind, worked like a supermarket: When you pull a milk carton off the shelf, a new one shows up right behind it. The same causal structure is true for all manufacturing, even for things as complicated as cars. A customer purchase starts the production process, and the customer must get exactly what they order, at the quality they expect, basically instantly.

In other words, customers “pull” the product out of the factory. Customers cause production to happen. More broadly, customer pull is the causal force in business. Think again of the supermarket analogy - in Ohno’s mind, the whole business exists to deliver the carton of milk you want the moment you reach for it on the shelf.

“Push” and “pull” are incompatible ways of understanding the physics of business. This turns out to be massively important: they generate businesses that look and act totally different.

In “pull”, business optimizes around delivering what customers order and expect - customers’ orders and expectations are the business’s highest-level constraint, they are the force that shapes every action of the business. In this model, no part of a business can be understood without reference to how the customer initiates it.

In “push”, we don’t perceive the customer’s order as the highest-level constraint. Which means it would be weird if we optimized for it… making it a happy coincidence if we deliver for customers. In fact, “push” almost guarantees we don’t deliver for customers. Here’s how.

In Taylor’s time, we saw massive increases in output when “push” optimized for hitting our plans and goals. But if we think our plans and goals cause outcomes, what forcing function keeps our plans and goals from being unrealistic or drifting away from delivering for customers? In the case of American car manufacturers, they optimized for hitting production plans, and when production plans were missed or had second-order consequences (e.g., quality issues, excessive inventory, wrong “mix” of production), they misdiagnosed their problems as execution problems and layered on more management, more measurement, etc. “Push” caused them to evolve to be bureaucratic and sluggish.

Since Taylor’s time, businesses have experimented with optimizing for a variety of things - our vision, the product we want to build, what Wall Street wants, culture, some new hip management fad, and on. These are all doomed for the same reason. In the case of modern startups, for example, we often optimize for the product idea we want to exist; when customers don’t buy, we misdiagnose it as a messaging problem, a sales problem, or a “we need to build more” problem - the real problem is invisible to us. Inside the “push” model, where we don’t see customers as the primary constraint, it is impossible for us to correctly understand why the business isn’t working. We only see half of the equation - the non-causal half!

So, by default, “push” causes failed startups, bloated bureaucracies, bad customer experiences, and bad products. We behave as if customers are an afterthought, despite any and all slogans about customer centricity and quality. There is no forcing function to focus on customers. It is only by heroic effort, usually by a (highly disagreeable) founder, that this does not happen under “push”. You can see this in basically every modern business or organization - it’s why you’re still on hold with customer support right now.

This entropy is not endemic to the “pull” model, because “pull” forces us to focus on customers and ask one question repeatedly - “Did we deliver what they ordered, to their expectations?” This generated all the manufacturing process innovations out of Japan you’ve heard of - Lean, Kanban, SMED, etc.

The distinction between “push” and “pull” represents a foundational evolution to business theory, roughly equivalent to the Copernican revolution. It enables modern business to evolve from the default state of “disappointing the customer” to one of “not disappointing the customer.”

However, this evolution in theory is not broadly understood. Most people think that Japanese engineers just invented some useful manufacturing techniques and quality practices. They miss the point - that these techniques were all generated by the “pull” model, a new foundational model of business! The only person I’ve seen describe it clearly, and the person I learned this from, is John Seddon (in Freedom From Command and Control, Chapters 1-2), and he is far outside mainstream business thinking.

Because this is not understood, the “push” model is still the dominant business paradigm today. We think our plans and intentions cause outcomes; if it works in our head, it will work in the world. Marketing and sales are things done to the market, to convince them to want the product we’ve created. We are just one killer offer, one unbelievable value prop, one more feature, one psychology hack, one growth tactic away from success. This is a seductive fantasy, and it’s the water we swim in.

We have to evolve past “push”. But “pull” is not enough, either.

Pull vs. PULL

The “pull” model shifts our optimizing function from “hitting our plans” to “delivering what the customer orders.” But does the customer order represent what customers want? Or is there something upstream of the customer order that we should really be optimizing for?

Bob Moesta won’t admit this, but he is behind a shocking percentage of successful new products in recent decades. His big insight is that customer orders are “requests for supply”, they are not “what customers want” - they are not demand.

The best way I’ve found to give you the intuition for this is by explaining why feature requests aren’t demand. When a customer submits a feature request, it seems like there is demand for that feature - they are literally demanding the feature!

But take this example (longer treatment in this post):

A customer of a project management software submits a feature request for a “permissions feature” - so it seems like she has demand for a permissions feature

But when interviewed, she explains that the reason she submitted this feature request was that a contractor on one of her projects archived the project, not realizing doing this would archive the project for everybody on the project. Everybody on the project freaked out, and this caused her to submit the feature request for a “permissions feature”

It turns out, she doesn’t want a “permissions feature” - that’s supply she’s requesting, her real demand is - “prevent one person from unknowingly archiving the project for everybody”

This demand can be solved with a complex “permissions feature” (which would take months to build), or a simple pop-up when someone clicks the archive button saying “are you sure? this will archive the project for everybody,” (which would take a few hours AND be better-fit supply for the customer’s actual demand)

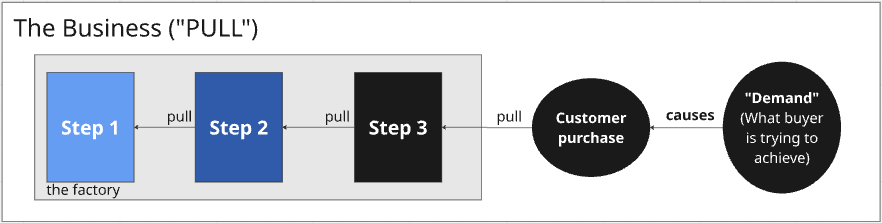

Now we can actually see the demand side. This demand side causes feature requests, like in the example above, but it’s the same thing that causes purchases. The demand side is, roughly, “what a customer is trying to achieve in their life.” It is not “desire for a product”, it is product-agnostic - like “prevent one person from unknowingly archiving a project for everybody” is agnostic to supply like the “permissions feature”. But demand creates the feature request, it causes it.

Demand is causal: The demand side generates the customer order… if and only if our supply fits their demand.

So: Businesses need to optimize for demand, helping a customer achieve this thing they’re trying to accomplish in their life. This is upstream of their order, our production process, and our product.

If we ignore demand and just focus on the customer order via the (lowercase) “pull” model, we can produce what customers order at high quality and low cost. But as we’ve seen in the “feature request” example above, how likely is the customer’s order to fit their true demand? As a result, how likely are we to build something that fits what customers really, truly want?

Very, very unlikely. At best, we will produce Toyota Corollas: solid products that compete admirably on price and quality, that win because the bar is low - everyone else is disappointing customers. What we build with the “pull” model alone can’t possess the mystical power of an early iPhone, an early Starbucks store, an early Tesla Model S, a Rogue barbell, a Philips OneBlade, or some other product experience that actually stirred your soul, that “fit” some deep need you couldn’t quite articulate, that make you feel like someone finally understood you and built something just for you.

When products fit demand very well, we behave as if we really want them, we might even obsess over them. On the other hand, when I bought my Honda, I did not do it because I wanted a Honda. I did it because I couldn’t find a good enough reason not to buy a Honda. I walked into the dealership with a feeling of resignation; I was merely accepting the least-bad option.

This doesn’t have to be our fate. There is no law of physics that says products can’t be high quality, affordable, and magical. In fact, capitalism is structured to massively reward these kinds of products - the fact that this is not happening in so many parts of the economy is a symptom of business theory being stuck. Capitalism, if we business folks get our heads on straight, is the most powerful, most positive human invention of all time. It is a fusion engine for progress. Yet because business theory is stuck and lots of businesses suck, this argument doesn’t land.4

Every entrepreneur, deep down, wants to build something wonderful. Something that customers rave about, something that dominates the market because customers rip it out of our hands. We can’t do this if we’re operating with the wrong model of the physics of business - we need to focus on demand.

Bob Moesta created the Jobs to be Done theory to try to explain demand (and also to explain why he is so uniquely good at creating new products that take off); I created the PULL framework because I seem to be too dumb to understand Jobs to be Done.

So we wind up with the (uppercase) PULL model, which, I think, finally focuses us on the right thing:

This is, I think, the true model of the physics of business. When we embrace it, building something magical becomes less unintuitive. We finally understand how to “build something people want.” It ain’t easy, but at least we aren’t ass-backwards.

That said, there is a TON more work to do in order for us to actually understand PULL; I feel like I’m just scratching the surface. So I’ll keep building and keep writing. See you next week, when my post will be far less theory. I hope.

PS: Work with me!

If you’re trying to find product-market fit and figure out sales, let’s chat! Three ways I can help:

I can review your recorded sales calls to help you figure out why customers aren’t pulling your product out of your hands… and what to do about it. This is a super fast, lightweight way to get my help fixing your sales call, pitch, demo, execution, etc.

I’m behind dozens of $0-$1M ARR journeys as a PMF advisor. If you’re looking for ongoing support from someone who’s made this happen a bunch of times, reach out - I have limited bandwidth for Q1 so please reach out ASAP!

I run PMF Camp - a bootcamp (next starts in Feb!) and weekly live event series where we tear down founders’ sales calls and build your intuition for what customers want and how to sell.

If you’re interested in any of these, request time HERE or email me at rob@reframeb2b.com. If you want more info and testimonials, see HERE.

This and other pieces of this section come from John Seddon’s book, Freedom from Command and Control. Chapters 1-2 should be required reading.

For a detailed history of this, check out The Reckoning

Again, Freedom from Command and Control. I’m going to keep referencing it until you read it.

There are so many other downstream consequences of push vs. PULL I wanted to write about… but this post is already too unwieldy. My personal hobby horse is that “push” is why houses built today are all uglier than houses built 100+ years ago.

Can’t help but wonder whether there are psychological/emotional factors beyond the outdated theory. We’ve had JTBD and customer research gesturing at what you explain for 2 decades and more - and often being ignored.

Maybe the clarity of your explanation will cut through?! On the other hand, we just did an episode about how increased clarity can increase resistance - when people don’t understand it’s often not that they don’t get the concepts, it’s that they can’t countenance the implications. (Ep. 130: The Sinclair Effect and the Winkler Constraint)

Also gotta drop in a note that Taylor seems to have been telling porkies about pig iron, and was at least exaggerating if not inventing the stories that led to the school of business. Not to say he was wrong, just that we need to bring salt.

Ok fine. After I finish this geek fest Warhammer 40k novel, John Seddon it is 😅